An Introduction to a Veil of Silence

Omissions, Bias, and Constitutional Rectitude in the 1975 Dismissal

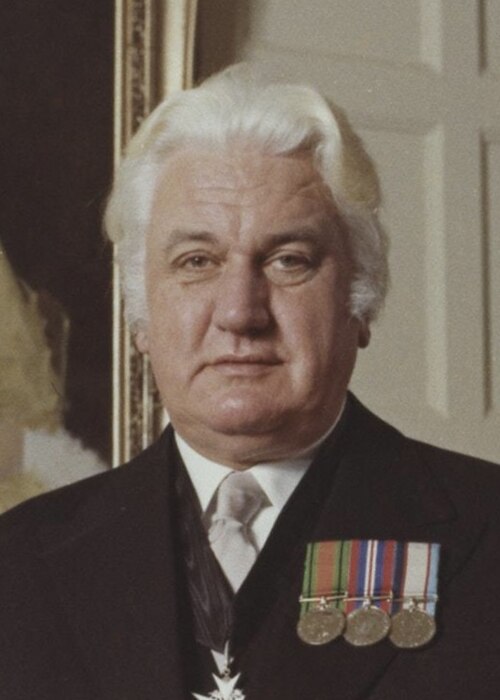

In the annals of Australian political history, few episodes have been so relentlessly weaponised for partisan ends as the dismissal of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam by Governor-General Sir John Kerr on 11 November 1975. Yet, a conspicuous silence, or, more damningly, a cascade of convenient omissions, has long characterised the narratives peddled by the left-leaning legal fraternity and their journalistic acolytes within the Labor-aligned intelligentsia. These custodians of progressive orthodoxy have assiduously defamed and vilified Sir John, reducing a principled constitutional actor to a caricature of drunken opportunism, while eliding the chaotic governance of Whitlam’s administration and the unequivocal legal foundations underpinning the dismissal. This selective amnesia not only distorts historical truth but reveals the ideological predispositions of its purveyors.

Geoffrey Robertson’s Biases and the Media’s Silence

A salient illustration emerges from Geoffrey Robertson’s 1987 interview with Sir John, conducted for the BBC series Hypotheticals. Robertson, an eminent barrister and darling of the chardonnay-sipping left, whose oeuvre often aligns with Labor’s cultural milieu, probed the appointment of Governors-General with a veneer of impartiality that barely concealed his bias.

Robertson posited that future incumbents ought to be drawn exclusively from the ranks of constitutional lawyers, citing Sir John’s successors, Sir Ninian Stephen and Sir Zelman Cowen, as exemplars. This insinuation implicitly demeaned Sir John’s own credentials, which he deftly rebutted by underscoring his prior tenure as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of New South Wales, a pinnacle of judicial distinction that the left’s smear campaign had reductively distilled to “working-class origins and alleged inebriation.”

Robertson’s line of questioning betrayed a predilection for elevating Labor-favoured jurists while marginalising Sir John, whose working-class ascent and non-elite pedigree evidently grated against the progressive establishment’s preferences.

On the constitutional legitimacy of the dismissal itself, Robertson’s commentary further underplays critical precedents and textual imperatives. He glosses over the 1932 dismissal of New South Wales Premier Jack Lang by Governor Sir Philip Game, an analogous exercise of reserve powers that averted fiscal catastrophe without judicial intermediation. More egregiously, Robertson and his ideological kin ignore the Australian Constitution’s express provisions empowering the Governor-General to dismiss a Prime Minister under specified exigencies, without mandating prior judicial review. This is no mere convention, as the left often frames it to impugn Sir John’s actions, but a deliberate textual endowment designed to safeguard parliamentary supply and governmental stability.

The vitriol heaped upon Sir John was not merely unjustified but outrageously disproportionate, especially in light of the unruly, unwieldy Whitlam Government teetering on the precipice of disaster. Had the Khemlani loans affair succeeded, wherein Treasurer Jim Cairns and Minerals and Energy Minister Rex Connor pursued billions in unorthodox petro-dollar borrowings from the shadowy Tirath Khemlani, an unregulated finance broker of dubious repute, the nation’s economy might have been irreparably compromised. Khemlani’s involvement exposed sensitive state security matters, including potential ties to Middle Eastern intermediaries, thereby bolstering the advisory roles of Governor-General Sir John and Chief Justice Sir Garfield Barwick. Whitlam’s administration, marred by ministerial resignations, supply blockages in the Senate, and fiscal impropriety, had forfeited the confidence essential for effective governance. Sir John’s intervention was thus a constitutional bulwark against impending calamity, not the capricious betrayal portrayed by Labor’s apologists.

Constitutional Legitimacy for the Sacking

The Australian Constitution vests the Governor-General with untrammelled executive authority, including the prerogative to dismiss a Prime Minister bereft of supply or parliamentary confidence. That these clauses eluded the ostensibly incisive Geoffrey Robertson, whose 1987 interrogation of Sir John Kerr exposed more about his own partisan blind spots than any constitutional lacuna, speaks volumes.

Geoffrey Robertson manifestly lacked both forensic rigor and emotional or political detachment in his advocacy regarding the Whitlam dismissal. He gravely undermined his own position by proposing that figures such as Sir Ninian Stephen or Sir Zelman Cowen, both eminent constitutional jurists who ascended to the governorship-general, should serve as exemplars for entrenching the office within the Constitution, only for Sir John Kerr to be abruptly appended to that roster. Few recall that Kerr himself had been Chief Justice of the New South Wales Supreme Court, a distinction Robertson obfuscated by impugning him as an inebriate, sheltering behind the theatrical veneer of ‘The Dismissal’. The record abounds with further evidence. The media relentlessly vilified Kerr for executing one of the governorship-general’s most solemn duties: intervening against a government that had spiraled into utter chaos and profound disconnection from reality. Had the Whitlam administration truly commanded widespread approbation, it would scarcely have suffered such a resounding electoral annihilation in December of that year.

Express Powers:

- Section 61: “The executive power of the Commonwealth is vested in the Queen and is exercisable by the Governor-General as the Queen’s representative…” This establishes the Governor-General as the locus of executive authority, encompassing reserve powers to act in crises.

- Section 64: “…The Ministers of State…shall not exceed seven in number, and shall hold office during the pleasure of the Governor-General.” This explicitly renders ministerial tenure, including that of the Prime Minister, subject to the Governor-General’s discretion (“during the pleasure”), permitting dismissal without judicial oversight when supply fails or confidence is lost.

- Section 28 (in conjunction with supply crises): While not directly prescriptive, it underscores the necessity of appropriations for government functioning, implying the Governor-General’s duty to resolve deadlocks, as occurred when the Senate deferred supply bills in 1975.

- Section 57 (double dissolution mechanism): Though not invoked for dismissal per se, it reinforces the Governor-General’s role in resolving parliamentary impasses, which Sir John navigated by proroguing Parliament and calling an election post-dismissal.

These provisions, rooted in the Constitution’s federation compact, affirm that Sir John’s actions were not only lawful but imperative. The left’s enduring campaign of calumny against him serves less as historical analysis than as ideological retribution, obscuring the Whitlam Government’s self-inflicted wounds and the Governor-General’s steadfast defence of democratic integrity.

Brutus